Two years later, Ghost Ship fire stirs haunting memories

Friends, family gather for memorial but questions of blame, responsibility remain

By Erin Baldassari

ebaldassari@bayareanewsgroup.Fcom

OAKLAND » There was Cherushii with her pink, turquoise and blond hair. Barrett with his fearless sense of adventure.

Sweethearts Alex Vega and Michela Gregory, who died in each others’ arms. But also Cash, Amanda and Ara. Griffin, Joey and Draven.

Thirty-six people who lost their lives trying to escape a warehouse-turned-tomb.

Several dozen friends and family members returned Sunday to the corner of 31st Avenue and International Boulevard, where a four-alarm fire ripped

Benjamin Burke, left, and Alexander Friend, both of Oakland, share a moment in front of the Ghost Ship building on Sunday. where 36 people died in a fire at a dance party two years ago. Mourners gathered for a procession to Lake Merritt to remember the dead.

PHOTOS BY DOUG OAKLEY — STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Photos of some of the 36 people who died in the fire adorn a shrine in front of the burned out structure on Sunday.

through a warehouse in the city’s Fruitvale neighborhood during a dance party, catching party-goers by surprise and trapping dozens inside.

Sunday marked the twoyear anniversary of the blaze, the deadliest building fire in Oakland’s history.

But, for Lori Ford, this year’s anniversary was even more devastating than the first. Not a day has gone by that Ford hasn’t thought of her sister, Michele Sylvan, 37, and Sylvan’s creative spirit, her ecstatic dance moves, her silkscreen paintings or her DIY dressmaking.

“Now that more time has gone by, it’s sinking in that her life is gone,” Ford said. “And, I haven’t seen in her in a while.”

She paused, tears rolling out from beneath sunglasses, “That makes me really sad. I miss her.”

Jordan Scott, of Oakland, hasn’t managed to shake the eeriness of losing his friend, Barrett Clark.

“It’s a strange void,” he said. “It wasn’t anything anyone was expecting.”

Not expecting, but not entirely surprising. People involved in Oakland’s arts scene knew it wasn’t a great place to host events, Scott said, that the labyrinth of wooden furniture and a staircase made of pallets wasn’t the best design.

“Everybody knew it was an accident waiting to happen,” he said. “This was often the last option.”

For years before the fire, rising property values had been attracting investors eager to convert warehouses into luxury lofts or marijuana grow houses. And the dwindling number of safe spaces left for artists to use as affordable live/work studios led people to take more risks, said David Bernbaum, whose brother, Jonathan Bernbaum, was killed in the fire.

Then, just days after the fire, dozens of people living in converted warehouses began receiving eviction notices. That didn’t help, either, Bernbaum said.

“Is an empty warehouse any safer?” he said. “If you clear-cut a forest so it doesn’t burn, is that any better?”

In the weeks and months after the fire, the question of who to blame ignited and grew. How could an artists’ collective with upwards of 20 people living there thrive for years without city inspections, despite repeated visits there by police and firefighters?

A criminal case has focused on two defendants: Derick Almena, the eccentric leader of an artists’ collective and master leaseholder of the Ghost Ship warehouse that was decorated in an elaborate labyrinth of wooden furniture; and Max Harris, who helped organize the electronic dance party the night of the fateful fire and who allegedly blocked one of the exits that could have helped the partygoers escape.

A judge recently threw out a plea deal for Almena to serve nine years and Harris six after pleading no contest to 36 counts of involuntary manslaughter after two days of gutwrenching testimony from family members. A trial is expected in the spring.

But, a civil case casts a much wider net when it comes to laying blame. In addition to Almena and Harris, the city of Oakland, Pacific Gas and Electric Co., and the building’s landlord are all named in the suit, which was filed on behalf of 80 plaintiffs and alleges officials were aware of the electrical dangers at the warehouse but failed to keep the building safe.

Between mid-2014 and the deadly fire, police visited the warehouse and adjacent properties nearly three dozen times, responding to thefts, reports of child abuse, a stabbing, gun threats, drug sales, illegal housing and more. Despite the earlier warnings, no record of an inspection for the building was ever found.

Alameda Superior Court Judge Brad Seligman ruled in May the city had a “mandatory duty” to ensure safety inside Ghost Ship — leaving the city liable for the 36 deaths. The state Supreme Court recently upheld the decision when it declined to take the case. The building’s landlords, Chor Ng and her children, property managers Kai and Eva Ng, have been mum since the fire, but spoke for the first time recently via court filings on the deadly blaze. They blamed a contractor who lied about having a valid license and performed shoddy electrical work — a likely cause of the blaze — while Almena broke his lease by renting out living spaces inside the commercial warehouse.

But no amount of fingerpointing will bring back the dead, said Szonic Allure, who lost two friends in the fire.

“There’s no one finger to point,” he said. “It was a combination of unfortunate events.”

If anything, the fire has made people in Oakland’s artistic community more resolved to continue gathering in ways that reaffirm values of non-commercial exchanges, independent thinking and open self-expression, Scott said.

Though that doesn’t mean nothing has changed, said Nikole Lent, a member of the Underground collective, which helped host Sunday’s memorial. She had worked events at the Ghost Ship warehouse and lost four friends in the fire, she said. Sunday marked the first day she had returned there since the blaze.

Before the fire, Lent might have pushed aside concerns that a space was unsafe.

“Not anymore,” she said. “Now, if we feel like a venue is unsafe, we’re like, ‘It’s not going to happen.’ We need to be accountable to each other.” Contact Erin Baldassari at 510-208-6428.

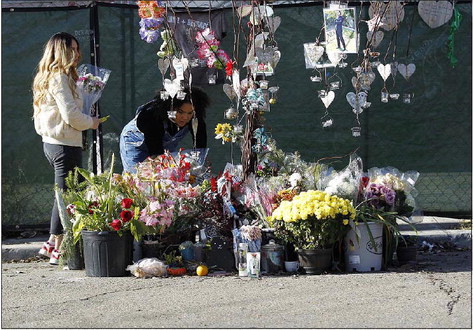

Heidy Meza, left of Richmond, and Patty Herrera of San Francisco, leave flowers in front of the Ghost Ship building on Sunday in Oakland where 36 people died.

DOUG OAKLEY — STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER